Creating The Definitive Muscogee 221 Insignia Guide – the Author’s Story Part 1

History has always been a passion of mine. Ever since I began collecting patches as a youth, I have often wondered about the stories behind them. I gained a lot of this knowledge early on by attending the patch auctions that Muscogee held at each of its fellowships and listening to the narratives the auctioneers would recite prior to opening the floor for bids.

Back then we had some really great youth running the auctions--Jonathan Hardin immediately comes to mind--and they were very enthusiastic about each item, not just the rare ones that they knew would sell high. They’d hold up a patch from a fellowship that took place years before I was ever even tapped out, then they’d point to someone in the room who was there at that event: an older Scout, or perhaps an adult in the back row who was busy eating a bowl of ice cream from the cracker barrel.

Back then we had some really great youth running the auctions--Jonathan Hardin immediately comes to mind--and they were very enthusiastic about each item, not just the rare ones that they knew would sell high. They’d hold up a patch from a fellowship that took place years before I was ever even tapped out, then they’d point to someone in the room who was there at that event: an older Scout, or perhaps an adult in the back row who was busy eating a bowl of ice cream from the cracker barrel.

“Tell us about this weekend,” they’d say, “tell us what happened to you at this event!” Sometimes the story we’d get would be about how that patch represented the weekend they held their Vigil. Other times it would be about how terrible the food was at the event (Dixie “Death Stew,” anyone?) or how the weather was so bad that most Scouts went home and only a few made it through the entire weekend at camp. Such was the case at the 1993 spring fellowship, affectionately referred to as the “Deep Freeze” weekend, and later commemorated by a special second patch depicting a polar bear.

These stories are what kept me coming back, and I knew there were plenty more stories to be told. The problem was that as the years passed, the people who had told these stories in the past began to slowly disappear. Some got older and went to college, some entered into new careers or started families, and others passed away. I realized that unless someone took it upon themselves to document these stories, future generations would never get a chance to hear them the way I heard them.

But there was also a second problem that I felt needed solving, and that was the lack of quality information readily accessible to collectors. When I began seriously assembling my own Muscogee collection as a youth, I quickly learned that there were some tidbits of information that were seemingly relegated to a very select few individuals. Only a handful of people knew anything about certain issues or variations, and I felt this should be common knowledge.

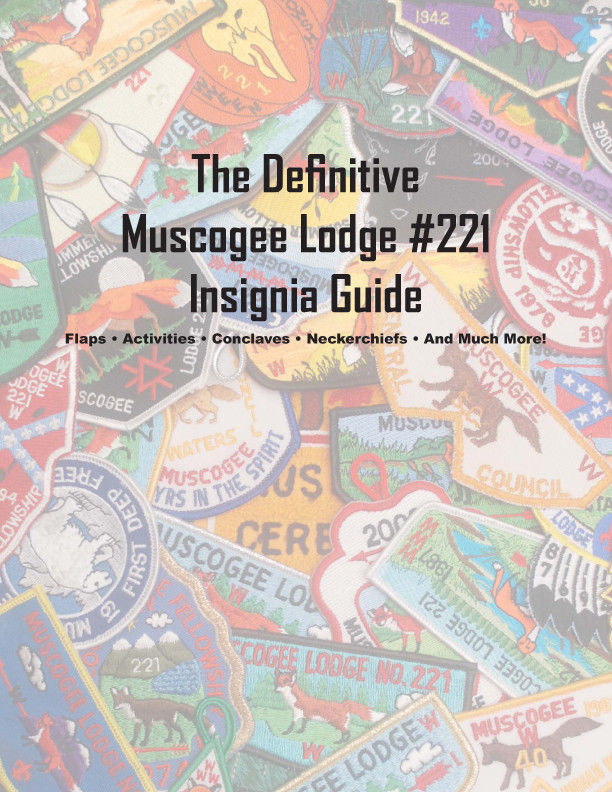

And so it was a combination of my desire to preserve lodge history while simultaneously facilitating the hobby of patch collecting that led me to undertake my largest personal project to date. Though for reasons that I will explain in my next segment, I knew that it would not remain a personal project for long.

I knew the best format for my venture would be a book of some sort, but I’d never actually written anything longer than a 20-page term paper in my undergrad years at USC. Those papers were in MLA format with no images, and all the resources required for research were readily available online whenever I cared to access them. But because I didn’t have a complete Muscogee collection myself, my only option was to borrow the pieces I was missing from other collectors to scan and document. While I didn’t particularly like the idea of relying on other individuals to create this book that I had envisioned, I knew it would be necessary.

I will admit that there was a lot of personal pride on my part with not wanting to include anyone else in the project, but there were practical reasons as well. It’s true that I wanted this to be my work, something that I made. However, I also didn’t want to have to fight the “too many cooks in the kitchen” battle when making decisions about the book’s format, what to include or exclude, how to distribute it once it was done, &c. I wanted the number of opinions and hurt feelings to be kept to a bare minimum.

So the first “cook” I enlisted help from was Jeffrey Cook: another Muscogee collector whom I’ve known for years. I discussed my plan with him, and he agreed that a book like this was a good idea and something that was much needed in the community. He also agreed to come over to my house with segments of his collection on nights when our schedules allowed so that I could make scans and ask any questions I had.

The next individual I sought assistance from was Tripp Clark. A former Muscogee Lodge Chief and collector himself, Tripp has long amazed me with his vast knowledge of lodge history. What I particularly like about Tripp is that much of his information comes from firsthand experiences: he was very active in lodge leadership as a youth and still almost never misses a function even today. I knew that tapping into him as a resource would add a great deal of credibility to the book’s accuracy, and it also didn’t hurt that he and Jeff both have notoriety in the SR-5 collecting circles.

And so the plans were set into motion. I told Jeff and Tripp that I would be working on the bulk of the book alone, setting up formatting and filling in as many blanks as I could with my own collection, then reaching out to them after I had identified all of the holes. Unfortunately, I still wasn’t sure where to begin—I didn’t know what software to use, or how to go about publishing it once I was finished. Fortunately, Google had plenty of insight into all of these uncertainties.

This is Part 1 in a 3 Part series on his experience writing the lodge insignia guide

Contributed by the author David Goza

Please Leave Comments Below!

Hi Al! You are credited in the book as having designed the Ceremonies chenille, but not the ’96 NOAC. There were suspicions that the flap was also yours, but no one could confirm. If it was you, I will include this change in the next update. Thanks for the reply!

I have not seen yopur book. I have knowledge of a NOAC flap @96 the one with the very poor antwork (mine) and the Chenille which I designed as A REWARD ITEM for the lodge ceremonies team I also designed the black long sleeve “T” shirt with the fox on front. What did the fox say?